Motivations

As part of my coursework at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Western Switzerland, I participated in an applied cryptography class, in which one of the main projects was to build a secure, file-sharing application.

The application had to respect a strict set of cryptographic specifications, and had to be modeled and implemented in the language of our choice. Additionaly, a set of challenges (Forward/Backward secrecy, Post-quantum safety) were proposed for bonus points.

A more complete documentation of the cryptographic model can be found here.

Specifications

The application had to respect a set of specifications:

- The ability for users to send files to each other.

- End-to-end encryption, under the honest-but-curious threat model.

- Cryptographic support for large files.

- Temporal lock: The files could be downloaded at any time, but only decrypted after a specific moment in time, which was defined by the original sender.

- Multiple devices, simple authentication: The ability for users to log-in from any device, using only username and password.

Model

Note: All communications are assumed to be carried over a secure channel such as TLS.

Key structure

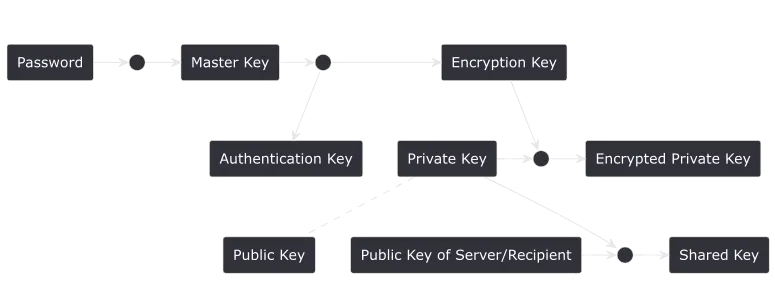

Multiple keys are used in the system to implement the given specifications. As described earlier, a user must be able to authenticate using only a simple username and password.

A first step is to allow authentication using the password. We can simply store a hash of the user’s password on the server, and use that as an authentication key. When a user tries to authenticate, the given password is hashed and compared to the stored hash.

Knowing the specification for the application, the user will most certainly need a private/public key pair to exchange signed and encrypted data with other users.

But how can we guarantee the user is able to retrieve a consistent pair of public and private keys, without having the server know this key pair? The answer: encryption. We can generate a random public/private key pair, and store only the encrypted version on the server. The user can then authenticate using their password and decrypt their key pair.

To avoid the server being able to decrypt the key pair, we will use an encryption key that the server doesn’t know, which excludes using the authentication key.

At this point, the user has to be able to compute both an authentication key and an encryption key, based on their password. The authentication is known by the server, and the encryption key has to stay secret, meaning we can’t derive the encryption key from the authentication key. The safest way to derive multiple keys is to use a hash key derivation function (HKDF), that allows to derive cryptographically safe keys from an initial hash.

The password will then be used to compute a master hash, which is then used to compute the authentication and encryption key. Those keys are then used to authenticate with the server, retreive the encrypted keys, and decrypt them. This is best visualized in the key structure diagram:

Encryption

To guarantee confidentiality, authenticity, and integrity, Timelock uses an authenticated encryption scheme. By combining XChaCha20 for encryption, and HMAC-512-256 for authenticity and integrity, we guarantee data confidentiality, authenticity, and integrity.

But to implement the timelocking feature, the message is not simply encrypted using a shared key between sender and recipient. If we did, the recipient would be able to download a file from their inbox at any moment (as required by the specifications), and decrypt this file instantly by computing the client-sender shared key.

In order to implement the timelocking feature, we must add an additional layer of encryption. When a user whishes to send an encrypted file, they first generate a new, random, one-time key, that will be used for this message only. They encrypt the file using this newly obtained key, then encrypt the key using the client-sender shared key.

The server then stores the encrypted message and the encrypted key separately. If the recipient whishes to download the encrypted message in advance, they are allowed to do so. Without access to the decryption key, the recipient isn’t able to decrypt the message. The recipient can then ask for the decryption key, which will be granted only if the unlock time has passed.

For the curious: A more detailled version of the documentation can be found here. The entire cryptographic model is laid out for each operation.

Implementation

The implementation is written in Rust, and presents as a simple CLI tool. Both the server and the client are available.

The implementation leverages Libsodium’s cryptographic primitives. Libsodium is a cryptographic library that implements most useful cryptographic algorithms, from hashes to authenticated encryption schemes, passing by elliptic curve cryptography.

You can learn more about the implementation on the Github repository, but here is a quick overview:

The project is built into three crates:

clientservershared

Which contain client code, server code, and shared code between client and server.

Cryptographic functions can be found in the respective crypto module of each crate.

All communications are carried out over TLS, using the native TLS implementation of each platform, thanks to the native-tls crate.

Libsodium primitive are imported through the libsodium_sys crate, and then wrapped by safe Rust functions.

The installation is described in the repository’s README file, and the documentation of the CLI tool can be accessed using the --help parameter.

Note: Even though the system cryptographically supports large files (XChaCha20 has no safety issues with large files), the implementation is not memory-optimized and will load the entire file in memory before encrypting/decrypting it, which may causes crashes with large files.